Saurabh Somani

While IPL 2024 rumbles on, those looking beyond the tournament have an eye on the 2025 edition as well. Particularly because there is a mega-auction expected before IPL 2025. With every game, there’s new options for who should be retained and who should be let go by each franchise. It’s speculation, but it’s done with as much passion as analysing Travis Head’s shotmaking or Jasprit Bumrah’s yorkers. Until the IPL decides on retention rules though, it will remain just that – speculation.

Whatever the retention rules are though, the mega auction remains the most significant event for shaping teams’ fortunes on the field. The next mega auction will be the sixth one, after 2008, 2011, 2014, 2018 and 2022. Each of the previous five were dramatic, pulsating, and path-breaking.

2008 – The Big Bang

The entire first season of the IPL was a tectonic-plate shifting event in cricket. The auction was held on two different days, but unlike future mega-auctions, not on consecutive days. The first round was on February 20. The next was on March 11.

It was towards the end of the most acrimonious tour that India had taken to Australia, the peak coming with the ‘Monkeygate’ flashpoint in the new year Test in Sydney. In the aftermath, it was thought that franchises might not be as keen on Andrew Symonds. He had been the central figure in the whole affair after all, and though his big-hitting, tigerish fielding and useful bowling were the complete T20 package, would any franchise risk investing in a guy who all of India seemed to want to point an injured finger at? As it turned out, those initial theories would set the template for how quickly T20 cricket – and the IPL in particular – render traditional thought obsolete. Symonds fetched a whopping $US 1.35 million in the auction, the second highest sum.

The highest went to the man who might conceivably still command top spot if he were to (inconceivably) enter the 2025 mega auction: MS Dhoni. He was bid for by all eight franchises, but Chennai Super Kings clinched the deal at $US 1.5 million, and an association like no other was born.

Teams had budgets of $US 5 million then. At the exchange rate then, Dhoni was bought for INR 6 crore. Which might seem small today, but it was 30% of the team’s budget, which would be INR 30 crore in today’s 100-crore budget auctions.

Dhoni was the highest priced cricketer, despite a lot of established stars being given ‘Icon’ status. That meant they were attached to the teams of their home states, and would be paid 15% higher than whichever player in their team had the highest bid. Which is how Sachin Tendulkar, Rahul Dravid, Virender Sehwag, Sourav Ganguly and Yuvraj Singh were part of the Mumbai, Bangalore, Delhi, Kolkata and Punjab franchises respectively. VVS Laxman had graciously withdrawn his name as an ‘Icon’ player for the Hyderabad franchise, thus letting them free up their purse for other buys. The ruthless nature of franchise cricket would be seen a year later when Laxman was unceremoniously dropped from the playing XI, but the Deccan Chargers surged to the IPL title in 2009 under Adam Gilchrist.

Only international players were auctioned in 2008. Domestic Indian players were signed outside of the auction, and to reinforce local identities for a new competition, each franchise had ‘catchment’ areas, whose players they would have first right to pick. The Under-19 players were picked via a draft. Teams drew lots, and Delhi got first pick. They went for left-arm seamer Pradeep Sangwan. He was a local lad, but the decision still shocked those in the room. Because Delhi didn’t pick the other local lad, who would also be the Under-19 World Cup winning captain. A young man answering to the name of Virat Kohli. Bangalore had the second pick, and thus was born IPL’s other great partnership.

The eventual man of the tournament, Shane Watson, as well as the highest wicket-taker, Sohail Tanvir, were not even part of the first round of auctions. The highest run-getter, Shaun Marsh, was signed barely a week before IPL 2008 began.

If that sounds like nobody had quite figured T20 out, that’s exactly what it was. 150 was a potentially winning score then, instead of being the score that franchises can now aim for at the 10-overs mark.

2011 – Retentions and rejections

This mega auction was of the kind that viewers today will recognise. Held over two consecutive days and broadcast live, with a whole lot of international stars going under the hammer. The IPL had become a bit of a juggernaut perhaps quicker than anyone had thought it would. When three years were up and it was time for a mega auction, the realisation came that some mechanism would have to be there to allow teams to hold on to certain players, and the player retention rule was born. But instead of letting market forces decide what a player’s price should be, the IPL came up with its own numbers. Teams could retain upto four players, and a pre-fixed amount would be deducted from their auction purse, which was $US 9 million this time. (approx INR 41 crore). If a team retained four players, they would lose $US 4.5 million from their purse.

The catch though: the amounts that teams paid each retained player could be whatever was privately agreed on. A team could in theory pay 10 million to each player if they wanted, but they’d be docked only the pre-fixed amounts.

Mumbai Indians went ahead and retained Sachin Tendulkar, Harbhajan Singh, Kieron Pollard and Lasith Malinga. Chennai Super Kings went for Dhoni, Suresh Raina, M Vijay and Albie Morkel. The combined number of players retained by the other six franchises was four: Kohli for RCB, Sehwag for Delhi, and Shane Warne plus Shane Watson for Rajasthan.

The absurdity of pre-fixed prices being docked from each franchise was shown up within the first half hour of the mega auction, when Gautam Gambhir went for $US 2.4 million and Yusuf Pathan fetched $US 2.1 million, both to KKR. Thus KKR were out $US 4.5 million in the open auction for these two players, while MI and CSK got four gold-plated players for the same amount. This was one of the more flagrant examples of the subversion of the salary cap, which was put in place to ensure a level playing field – and therefore a keener competition – for the IPL.

With a strong core in place already, MI could shell out $US 2 million for Rohit Sharma, while CSK got R Ashwin for $US 850,000. This auction had ten teams. The two new ones were the gloriously named and attired Kochi Tuskers Kerala, and the more staid Pune Warriors India. Both would be short-lived.

While the amounts spent for top players were headline-grabbing, the players who went unsold were equally newsworthy. The two biggest names in that heap were Sourav Ganguly and Chris Gayle. Ganguly, a spent force in T20s by then, wasn’t in any franchise’s wishlist. Gayle was in the midst of a standoff with the WICB, and there was little clarity on whether he would be issued the ‘No Objection Certificate’ that the IPL required from all players’ home boards. Both Ganguly and Gayle would eventually take part in the IPL as injury replacements, for Pune and RCB respectively. For Ganguly, it would grant him a fresh lease of life for one more IPL season. For Gayle, it would launch one of the most legendary careers in the format.

2014 – Uncapped Indians make an entry

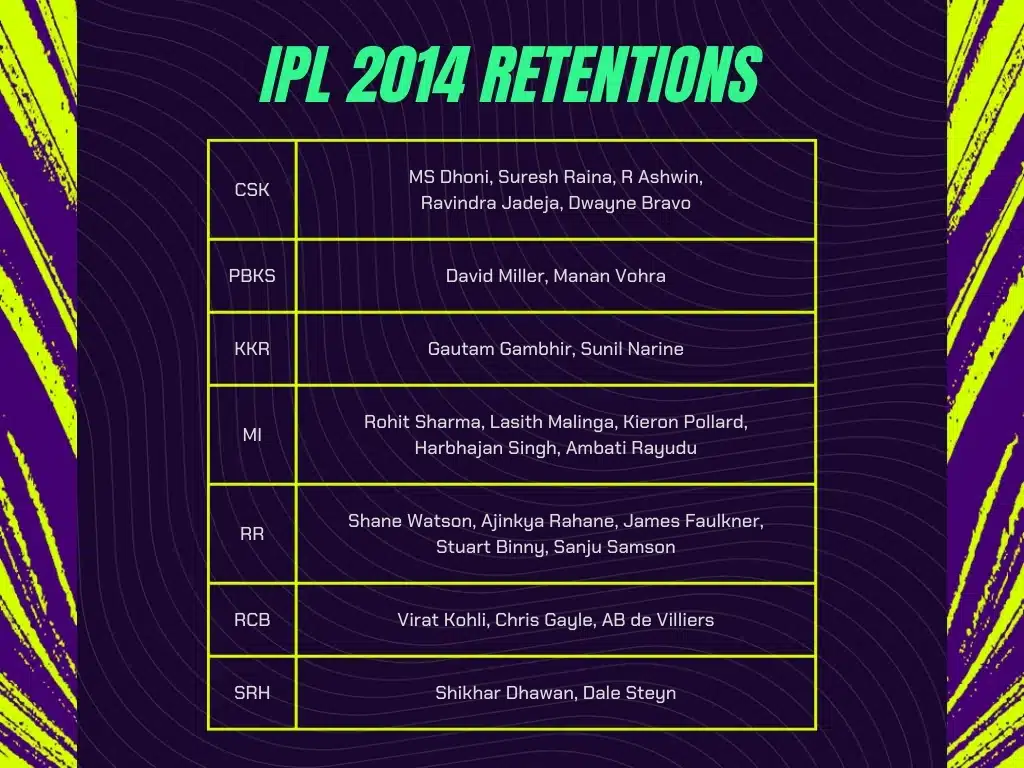

This time, teams were allowed to retain up to five players, and were also given ‘Right to Match’ cards, depending on how many players were retained. The auction amounts also moved from the American Dollar to the Indian Rupee, and each franchise had a budget of INR 60 crore. The IPL didn’t yet remove the loophole for retained players, although the amounts docked were higher since there were up to five retentions allowed. Retaining all five – as MI and CSK did again – would cost INR 39 crore. Rajasthan also retained five, but they had Stuart Binny and Sanju Samson, both at the time uncapped and thus attracting a smaller sum docked from their purse. Unlike in 2011 though, each franchise had players they wanted to retain this time, except for Delhi. With no retentions, Delhi got three ‘Right to Match’ cards, all of which were used. The other retentions were:

RCB broke the bank for Yuvraj Singh, buying him for INR 14 crore. Dinesh Karthik was the second-highest, at INR 12.50 crore to Delhi. Kevin Pietersen, by then into his permanent England exile, also went to Delhi for INR 9 crore, the most expensive overseas signing.

This was also the first auction in which uncapped Indian players went under the hammer. Previously, they had to be signed for fixed sums outside of the auction, which was a recipe for non-transparent dealings. It led to situations like Ravindra Jadeja being banned for IPL 2010, and Manish Pandey earning a four-match suspension in IPL 2011. The sums paid to uncapped Indian players were relatively paltry compared to the auction, with a maximum of Rs 30 lakh. The disparity between the fixed sum and the demand for players was shown up in 2014. Karn Sharma was the highest paid uncapped player at INR 3.75 crore, a greater-than-tenfold increase from what he would have got earlier. Several other uncapped Indians who had done well in domestic cricket had a significant hike in pay after coming into the auction.

2018 – The levelling of the playing field

The mega auction was held after four years this time, since it couldn’t be held in 2017. Why? Because both CSK and RR were banned for IPL 2016 and IPL 2017 for betting related offences, and two new franchises took their places for only those two years – Gujarat Lions and Rising Pune Super Giants. The auction budget was INR 80 crore. This time, teams could retain only three players each and they had two ‘Right to Match’ cards. CSK and RR were allowed to retain up to three players from their 2015 squads, as long as they weren’t part of any of the squads of the other six teams. Sanju Samson, who had been with Delhi during RR’s ban, could therefore not be retained by RR, and only Delhi could ‘Right to Match’ him at the auction. As it happened, RR did manage to buy Samson back for INR 8 crore. The CSK core had been with the two new teams so they could retain them. RCB made the surprising decision to go with Sarfaraz Khan as one of their retention picks, but the others were pretty much as expected.

The fewer retentions immediately made things more level. In addition, for the first time, franchises had to declare how much they were paying each retained player. Their auction purse would be docked from whichever was higher – the salary paid to the player or his retention slab. Thus RCB, who paid Kohli INR 17 crore, were docked that much, even though the first-player slab was fixed at INR 15 crore.

The other aspect that made this mega auction the fairest of them all was that the ‘legacy’ retention players were mostly all either retired or on a downward arc in their careers. After all, it had been 10 years since the inaugural edition. This auction thus had greater rewards for teams that had built a good core, rather than inherited one from previous auctions.

That MI put together an all-star team in this auction was a massive plaudit to their scouting and analytics staff. They managed to buy all of Pollard, Suryakumar Yadav, Ishan Kishan and Krunal Pandya in the auction, and their scouting brought them Rahul Chahar and Mayank Markande, both raw and uncapped then but who would go on to play for India.

2022 – Ten teams are here to stay

The budget had increased to INR 90 crore, and once again after 2011, there were ten teams competing against each other at a mega-auction. The existing eight teams could retain up to four players. Once they had made their picks, the two new teams could engage the services of up to three players from among all those remaining. That meant the newbies also began with strong cores.

Some of the retentions might not appear to make sense now, but almost all were backed by sound reasoning two years ago. Retentions are as much about what the player has done for the franchise as about what they potentially can do, and whether a franchise thought a retention would be more cost-effective than buying back the player in an open auction. Apart from a couple of doubtful calls, the franchises worked with what they had. In some cases, players did not want to be retained – a freedom they enjoy in mega-auction years. Otherwise, the franchise has first right of refusal. Some players exercised that freedom and moved franchises.

What has been apparent from one mega auction to the next though, is that now all franchises are on somewhat equal footing in key areas: personnel, analytics, scouting, and understanding auction dynamics. That doesn’t mean there won’t be bids and retentions that look horribly bad when 2025 can be seen with hindsight. But it does mean that the quest to discover a ‘hidden gem’ that no other franchise knows about will get more difficult. And that will make for a competitive, unpredictable IPL. Just like it has been through all these years.