For many years, playing at home has been perceived as an enormous advantage in international cricket. Certainly in Test cricket, the statistics are indisputable: The Ashes was won by the visitors just once in the 20 years between 2001 and 2021; India’s most recent series loss on home soil as of mid-2021 was at the beginning of 2013; and the list goes on. Many assume that this home ground dominance extends to the shortest form of the game, too, and if that belief holds true it could easily be argued that India deserves to be a stronger favourite for the 2021 T20 World Cup than what they are. But does it?

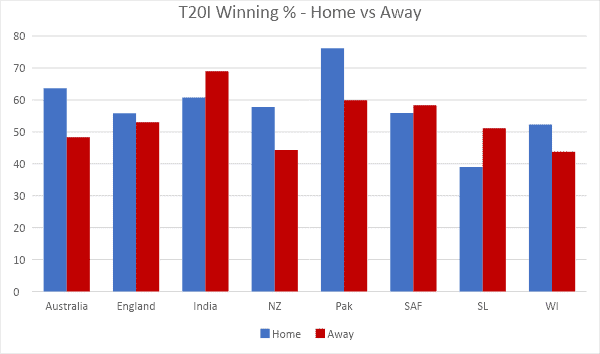

To better understand the correlation between home ground advantage and results, we looked at the records of the eight biggest teams in world cricket – Australia, England, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka and the West Indies. Since the shortest format of the game entered our lives in the mid 2000s, each of these sides has played well in excess of 100 T20Is. India and Pakistan have clearly enjoyed the most success in that time with win rates of over 60% while most of the rest of the pack have hovered at around 50%, but as the graph shows below, that hasn’t necessarily been a product of a dominant home record.

In fact, from the beginning of T20Is through until early 2021, just five of these eight teams have a superior record at home than away. A handful of those are statistically significant; New Zealand won nearly 58% of home games compared to just over 44% on the road in that time, while Australia batted at over 63% at home compared to around 48% away. Aside from those two, however, there isn’t a lot to write home about in terms of home ground advantage. Pakistan is the other which jumps off the graph, but it’s worth noting they played just 21 of their first 163 T20Is in Pakistan.

Other sides have actually been significantly better away from home, and our T20 World Cup hosts later this year are one such example. Over the course of the 14.5 years following their first ever T20I, India played 138 games. They were fairly dominant in that time, winning almost 66% of them, but surprisingly their record outside of India was noticeably better than within it; they won a solid 31 of 51 games at home, but a dominant 60 of 87 on the road. They’ve been installed as favourites for the T20 World Cup despite the fact that they are not ranked the highest T20 side in the world, and the fact that they will enjoy home ground advantage throughout the course of the tournament is likely a major reason for this.

Of course, while conditions in India are starkly different to what foreign nations like England and Australia serve up, surrounding countries such as Sri Lanka and Pakistan are much more similar. With that in mind, we thought it wise to determine whether a more significant home advantage existed against teams not from the sub-continent, and thus less familiar with Indian conditions.

As it turns out, there isn’t. For the purpose of this exercise we classed sub-continental teams as Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, all countries who experience much more Indian-like conditions at home compared to the rest of the teams India have played in T20Is. Against the rest – Australia, England, New Zealand, South Africa and the West Indies – India had a thoroughly mediocre record of 18-16 between 2007 and early 2021.

And things haven’t exactly changed in recent years. Early in 2021 they beat England 3-2 in a home T20 series while prior to that they beat the West Indies 2-1 in late 2019, but in neither of these series did they dominate. Harking back even further, they drew 1-1 with South Africa in India also in 2019, and lost 0-2 to Australia earlier that year. It’s a far cry from the almost unassailable advantage which playing at home is for them in Test cricket and which many assume translates to the shortest form of the game, and most likely means that India are closer to the chasing pack than bookmaker odds for the T20 World Cup would indicate.

There’s a couple of reasons which can probably help to explain this lack of home ground advantage in world T20 cricket, and more specifically in India. The first is simply that the pitches don’t have a chance to deteriorate in the same way they do in five-day cricket. This is particularly the case in the sub-continent; the significant turn as well as the lack of pace and bounce for which that region is known generally becomes more and more pronounced as Test matches go on – in T20 cricket, there is obviously far less difference between the pitch at the beginning of the match and at the end of it.

The other factor, and one which relates specifically to India, is the fact that so many international-level players participate in the IPL on an annual basis. As a result, they have plenty of chance to acclimatise to conditions and become accustomed to the differences which exist in the way the ball behaves in that part of the world. Heading into the T20 World Cup, this may play a major role – the IPL precedes it by just a few months, meaning many of the world’s best will have played high-level T20 cricket in India in the lead-up to the tournament, thereby minimising any home ground advantage the home side may have.

Clearly, home ground advantage plays a major role in international cricket – the vastly different conditions which exist across continents, as well as the raucous home crowds and various other intangible factors make sure of that. In the first decade and a half of T20I cricket, however, we haven’t seen it play nearly as significant a role as it has in Test cricket. This has particularly been the case in India, a country renowned in the longer form of the game as one of the most difficult to travel to, and as a result, the T20 World Cup set to take place in late 2021 could end up in the hands of anyone.