Estelle Vasudevan & Jarrod Kimber

On January 24, 2008, cricket was sold for $US 723 million. Lalit Modi, then the IPL chairman and commissioner, announced to the world the names and owners of the eight original IPL teams. Mumbai (of course, it was Mumbai) became the most expensive team, at nearly $US 112 million.

Some of India’s richest business tycoons like Vijay Mallya and Mukesh Ambani bought teams. But for the press, Modi led with the biggest Bollywood stars, Shah Rukh Khan and Preity Zinta as co-owners. English cricket has always been linked with random celebrities (Mick Jagger once did a project with Cricinfo to broadcast cricket in the 1990s), but they had never weaponised famous people’s love for the game.

The IPL became so big that there are stories of Bollywood agents getting fired for not getting their stars into the ownership of teams.

The base price for the teams had been set at $US 50 million each, so a total of $US 400 million was to be made, at minimum. They ended up making nearly twice that at the end of the auction – never-before-seen figures in the world of cricket. At that point, buying something in our sport was cheap. Suddenly, a hundred million dollars was being splurged on a concept.

The IPL wasn’t the first franchise tournament in cricket, it wasn’t even the first in India, that was the ICL. But in many other ways, it started everything.

The IPL, as Modi imagined, was to be a marriage between Bollywood glitz and cricket – India’s two favourite money-spinners. Instead of being run by dour cricket administrators, IMG would look after it. The idea was that it would be a mix of sports and entertainment. It was not supposed to be like normal cricket.

The BCCI had taken a lot of inspiration from US sports leagues like the NBA and MLB regarding the IPL business model. But they wanted to take a different approach to player recruitment.

In US sports, players moving into the major professional leagues are selected through a draft system or free agency. Each player’s salary is decided by which round of the draft they are picked in. The drafts themselves are a major event in the sporting calendar. The 2023 NBA Draft had an average viewership of 3.7 million, peaking at over six million during the first round.

The IPL could have gone down the same route, or even with no formal recruitment system at all – in which case teams would have been able to negotiate with players privately – similar to what happens in Premier League Football and Club cricket.

An auction though, now that would be a spectacle. And that’s exactly what the IPL wanted. Remember, this wasn’t just about cricket. This was about all-round entertainment. It had never been done before in the game. There were, and are still, a few grumblings about the idea of buying and selling players like livestock. But it worked. Here was another major event to add to the whole IPL experience, one with its own narratives and arcs. Splitting the auctions up into Mega and Mini Auctions just gave it yet another twist.

Despite its success, only three other franchise tournaments have adopted the auction since then, two closely related to the IPL – the WPL and the SA20, and the Lanka Premier League.

It’s now 17 seasons into the IPL, and the viewership for the auction continues to grow. The 2024 mini auction was the most-watched edition in history, with nearly 23 million in domestic viewership alone.

Viewership would mean nothing if not for broadcasting rights. This is the main cog of the IPL business model. Most leagues started making money from tickets. The IPL was lucky enough to start setting up for TV rights, and even online ones.

Modi gave away a lot of the early IPL rights for cheap overseas, trying to build extra interest in his brand. In the UK, he broadcast the league on YouTube for free at a time when most cricket administrators weren’t aware of the global video platform.

The BCCI sells broadcasting rights for the IPL for five-year cycles. The 2023-2027 cycle saw rights being sold for a total (including digital rights) of $US 6.2 billion, thrice the amount earned in the previous cycle. The BCCI retains 50% of the funds, and the rest is distributed among the franchises.

It’s no surprise that the broadcast value has grown so much – in 2008, the inaugural season, there were eight teams and 59 matches, while in 2024, there are ten teams and 74 matches. And this number is supposed to go up to 94 by 2027. In truth, if Lalit Modi was around he might have already tried to double that.

For the 2020 season, the BCCI claimed a cumulative 383 billion minutes watched across TV and digital platforms in India. And this is why the franchise model makes more money than international cricket. Even if Indian games still get massive audiences (sometimes more than IPL matches) you can never play as many. The IPL can play four matches on a weekend. And the other important thing about a league is that every time you turn on a TV for two months, you know there is a match on. The league structure won’t guarantee more eyes than internationals for a game, but it is consistent and has way more content. In the old free-to-air TV market, internationals made more sense. In a streaming and cable world, the league is king.

The first big change for cricket from the IPL was the sponsorship of in-game commentary. If you are old enough, you will remember a time when a six was just that and not a maximum. And that came out of the DLF maximums in IPL Season One.

You have the usual sponsored awards, but the IPL is always about innovation too. From sponsored boundaries to strategic timeouts and sponsors for umpires – every single element of the game is an asset because every brand wants a piece of the IPL. A catch was a Citibank moment of success.

That is all pretty normal now, but cricket wasn’t monetised like this before.

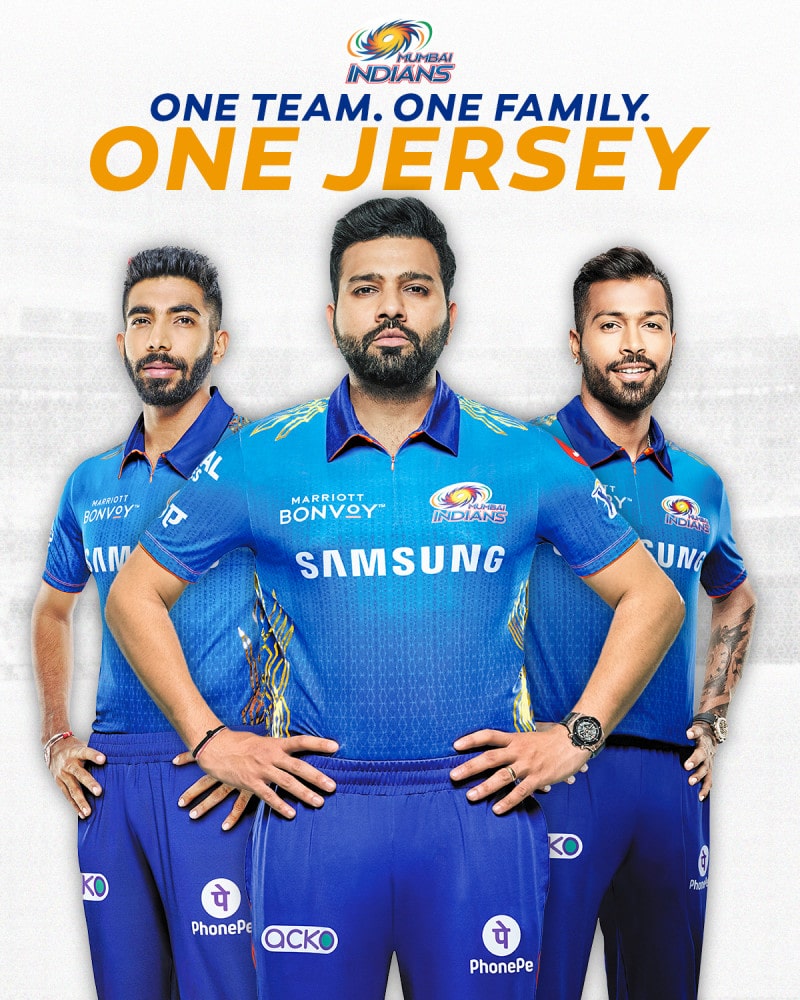

Each team has its own set of sponsors too. The Mumbai Indians have a total of 26 brands this season – 11 international and 15 domestic. These include 10 on their playing kit alone.

The TATA Group are title sponsors of the IPL for the next five years. The company renewed its association with the IPL until 2028 for a value of INR 2500 crore (that’s about $US 300 million), the highest-ever sponsorship deal in IPL history.

The industry that has done the best is fantasy cricket games. They did exist in some formats before, but Dream XI is now one of the biggest cricket products, and the IPL did that too (with some help from the fact it doesn’t count as normal gambling). My11 Circle is now an associate partner of the tournament itself, and fantasy sports revenue is projected for an incredible 25-30% growth compared to last season, reaching over $US 500 million in 2024.

The BCCI’s latest successful business venture is the Women’s Premier League. Better late than never they say, the WPL was launched in 2023 and two seasons in, is already the biggest women’s franchise league out there. And if not already, well on its way to being the biggest league for women in any sport. Many big sponsors from the IPL have secured rights for the WPL as well. Though nowhere near making as much money as the IPL yet, with the number of matches going up next season and a sixth team being added to the roster, revenue generation is expected to improve significantly in the third season of the competition.

But women were at the heart of the IPL from the start. Almost all cricket beforehand had been middle-aged (and above) men making a product for themselves. When the IPL was formed, the decision-makers were conscious about wanting women to come to grounds and watch on TV. It sounds weird now to say that appealing to 100% of the demographic, instead of 50%, was smart. But it really hadn’t been at the forefront of cricket’s thinking.

The financial growth of the IPL has been so exponential that the IPL decided it could spread its wings further into other leagues as well. Kolkata Knight Riders were the first ones to do it when they bought Caribbean Premier League side Trinidad and Tobago Red Steel (and renamed it Trinbago Knight Riders) way back in 2015. It wasn’t a trend that stuck immediately. The next franchise to buy a team was surprisingly Punjab Kings – they bought the St. Lucia Zouks in 2017.

It was in 2022 when things really caught on, with the announcement of the SA20. All six franchises are extensions of IPL franchises and the league itself is more or less an arm of the IPL. The ILT20 and the MLC in the USA are two other competitions that have a heavy IPL presence, further widening the league’s influence in the world of cricket. It’s the area where cricket’s franchise landscape is different from other sports.

All these other leagues are also – directly or indirectly – spinoffs of the IPL. The Big Bash changed after the IPL became successful and became a city-based franchise league. The Hundred is the same. The boards were making money before, but the IPL was building skyscrapers.

Many of cricket’s current problems are not from the IPL, but from the many copycat leagues that are trying to build their version of paradise, but in a media market 0.5% the size. Everyone wants their own grand domestic league.

But the IPL is a global league. It was inspired by the NBA and Premier League football. The IPL looked global in a way cricket never had. Not just by buying the teams. Non-resident Indians are also marketed to. Rajasthan Royals set themselves up as the “English” IPL franchise, even Point God Chris Paul owns a share of them. Cricket was always a global game that looked local, the IPL has exploded that.

A lot of what the IPL has done is purely marketing. At the Wankhede in 2012, there was a 25-foot-high picture of Aidan Blizzard. A Victorian cricketer that almost no one in Australia knew. A Test match in almost any city in the world is barely advertised beforehand. The IPL let everyone everywhere know this thing was happening. A lot of it is performative, but cricket’s biggest problem has always been celebrating and promoting itself. It preferred to set up a lemonade stand in a side alley and hoped people came there through word of mouth.

The IPL was an explosion of cricket love. It was harder for the older generation to understand it, what with the countdowns, spanish horns and team theme songs. But cricket was being celebrated, loudly.

All this has also created an environment where international cricketers are considering being freelancers as a serious option. With how franchise cricket is right now, a player can stand to earn far more than they do as contracted players for a given country, while playing a lot less cricket. Without the IPL, the idea of freelance cricketers would not have really made sense.

The West Indies greats Chris Gayle, Dwayne Bravo, Sunil Narine and the likes started it, but it took Trent Boult giving up his New Zealand Cricket contract in 2022 for the conversation to really enter the mainstream. Here was a key figure of a team that had won the inaugural World Test Championship and finished as runner-up in three limited overs World Cups, saying he didn’t want a full-time position with New Zealand Cricket so he could spend more time with his young family and make himself available for more franchise leagues. Many other players have opted out of Test cricket since then and it’s clear times are changing.

Players like Boult will not even really be freelance in the future, they will sign multi-league contracts. So instead of working for a board, their main employer will be IPL owners.

One of the reasons cricketers were underpaid (in all markets) was the lack of competition for their skills. Now a Nepalese spinner can play in Canada. The IPL opened up that market.

Not everything they have done has been great of course, but it has certainly been impactful. We’re unlikely to see the ECB rushing to do a deal with Saudi Arabia for a Desert Hundred. But so often when the IPL even hints at something, the rest of cricket rush there as well.

In January 2008, the IPL was a concept. Even the most optimistic person would have struggled to believe the IPL would be this big or influential. It is no longer simply a franchise league. At the moment it is what the business world calls a ‘decacorn’ – a privately held company with a valuation exceeding 10 billion dollars. That word was coined in 2013. The IPL has changed cricket business so much that we had to create new words for it.