Jarrod Kimber & Estelle Vasudevan

Tony Greig was a fantastically versatile allrounder. He averaged more than 40 in Tests when batting, and 32 with the ball. He could bowl seam or spin as well. But he never played for his country of birth, South Africa. Just as he was coming of age as a player, Australia, New Zealand and England had all stopped playing his team (South Africa had already banned themselves from playing India, Pakistan and the West Indies).

So Greig left to live in the UK, decades before the term Kolpak changed the game. He was good enough to play for, and captain, England. He was also in the second ODI ever played.

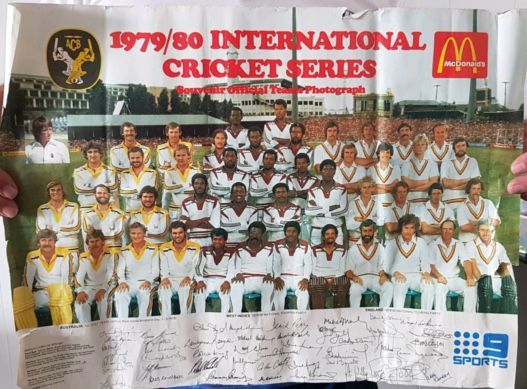

In the 1970s, limited-overs cricket was almost unrecognisable to what it is today. The playing kits were white, they used a red ball and every game was played during the day. It wasn’t even always 50 overs.

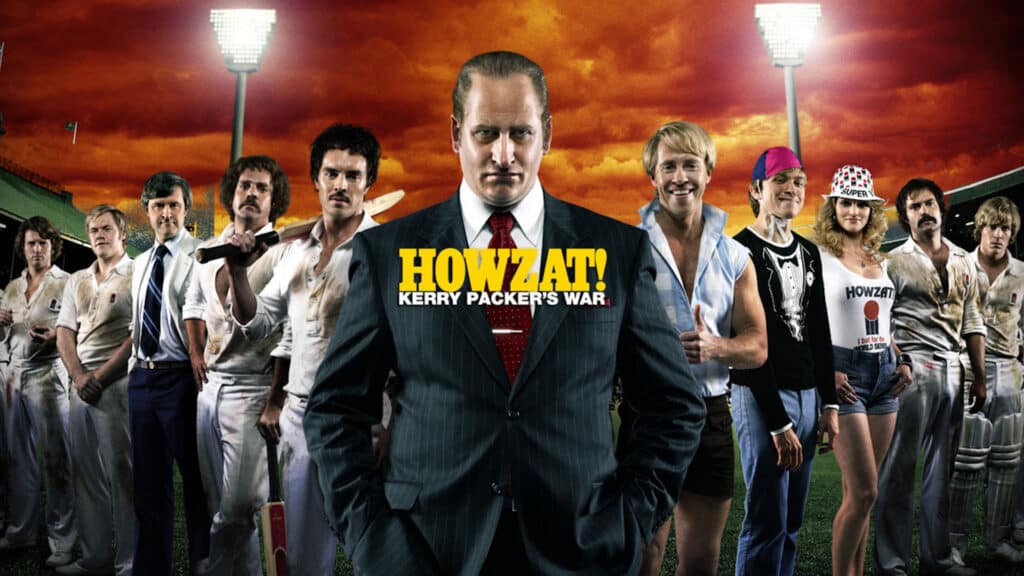

All that changed thanks to a man named Kerry Packer. His World Series Cricket revolutionised the game. A lot of the features they introduced in the tournament continue to be a major part of cricket today, including coloured kits and matches played under floodlights at night.

Why did Packer do it?

Packer wanted cheap Australian-made TV content and the game to look better when he watched it on his telly. Although Packer and his family had a huge stake in the Nine Network, they hadn’t been able to secure exclusive broadcasting rights to Australian cricket. When the ACB (now Cricket Australia) rejected his bids multiple times, the media mogul took matters into his own hands.

Packer decided that if he couldn’t buy the rights to the broadcasts, he’d buy the players instead, and plans were set in motion for an ‘exhibition’ tournament with global appeal. He managed to sign up some pretty impressive Australian, English, Pakistani and West Indian players, including Greg and Ian Chappell, Tony Greig, Clive Lloyd and Imran Khan in a covert recruitment drive. Even South Africans played, despite their nation being banned.

Of course all hell broke loose once the plans were leaked to the media in 1977. The lack of support from the sport’s governing body or the Australian board meant that World Series Cricket had a short life, but its legacy is one that has lived on. Kerry Packer went back to normal TV products, the players’ pay sadly regressed, but the white balls and pyjama clothing stayed.

To convince the players in the first place, Packer used Ian Chappell and Greig to recruit his cricketers. Three decades later, Greig would be involved in another rebel cricket league.

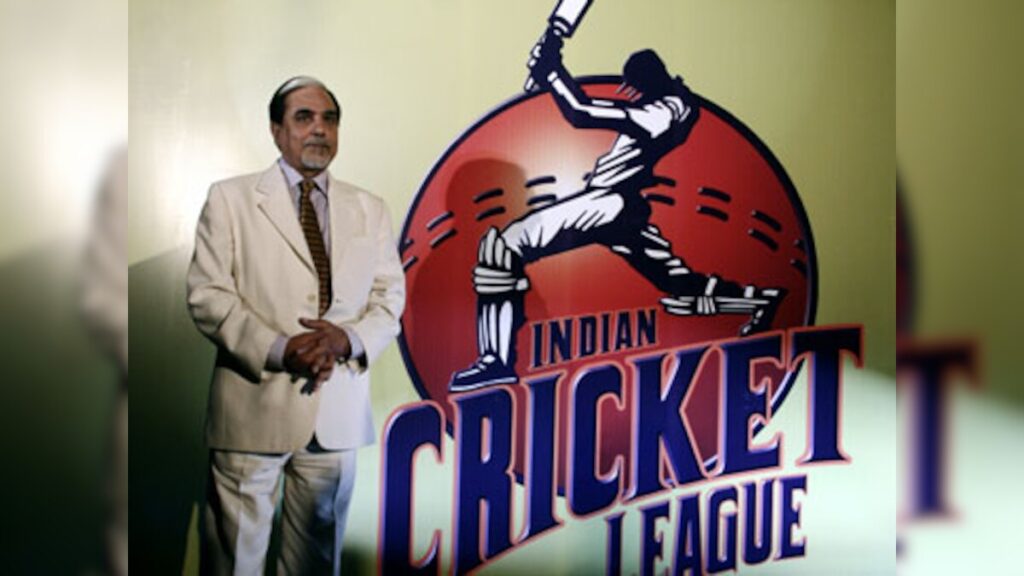

By the 2000s ODI cricket was massive, the biggest format really. But T20 cricket was fast moving up on the outside. And the first person to really commercialise this was again a TV station owner, this time Subhash Chandra, founder of Zee Telefilms.

After a historic World Cup win in 1983, Indian cricket steadily built into a giant. Over the 1990s and 2000s, they began establishing themselves as the most powerful board in the sport, they were certainly the richest by then. With India’s busy schedule, the BCCI got rich quick, unlocking the TV rights goldmine just before the 1996 World Cup. They didn’t get there without a fight, having to go to the Supreme Court for the right to sell monetise broadcasting, which until that point had been the monopoly of Doordarshan, the government television channel. There was even a time earlier when Doordarshan argued they should be paid to broadcast cricket.

Interest around international cricket was huge in the country, so broadcasters were frantic in their search to secure rights to Indian series. One of them was Subhash Chandra, who was happy to dish out some big money for exclusive broadcasting rights to Indian cricket. Unfortunately for him, the BCCI, wasn’t quite in favour of handing over the broadcast to Zee, even when they were the highest bidder.

Zee was desperate to get into the cricket broadcasting scene and so Chandra decided to launch the ICL, Indian Cricket League.

At the same time, the BCCI was unconvinced about the T20 format, which England had introduced in 2003. But then India won the inaugural T20 World Cup in 2007, they were World Champions for the first time since 1983 and in a format which they didn’t even play at the domestic level. T20s went from being seen as a gimmick, to being the next big thing.

The call for discovering new talent and the sudden popularity of T20 Cricket created the perfect environment to launch Chandra’s competition. But a couple of major hurdles lay ahead.

The BCCI was not about to hand over the reins of an entire format to a private entity (one they didn’t even sell the existing rights to). They refused to sanction the ICL and branded it as a ‘rebel’ league. Without the BCCI’s support, the ICC also refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the ICL and with this came the threats from boards around the world that players who participated in the tournament could kiss their careers goodbye.

Unlike the World Series – where Kerry Packer was able to sign up some of the biggest names in the game – Chandra was left with mostly players who had retired or who were close to the end of their careers. This was not ideal because he knew that the big names would be what drew sponsors and, thereby, the money in.

That’s not to say they didn’t have stars involved. Kapil Dev was the face of the league. Greig was some kind of Tzar – he joined Dean Jones and Kiran More as a board member. Damien Martyn, Chris Cairns, Inzamam-ul-Haq, Shane Bond, Lance Kluesner and Michael Bevan were some of the overseas signings.

But one of the main reasons the ICL didn’t take off with viewers was because they couldn’t secure those big-ticket Indian names, largely because of the BCCI. With no Sachin Tendulkar, Rahul Dravid, Sourav Ganguly or Virender Sehwag to draw in the crowds, it was a doomed enterprise.

Kerry Packer’s big advantage was that International Cricketers were not making much money then, so as soon as he dangled the carrot of riches, he bought pretty much every player he wanted (and also ignored guys he didn’t rate, like a one-man selection panel). That would translate to being fully professional, players were happy to secure a deal and find some financial stability. That wasn’t the case in 2007. Players were already fully (or fairly in some markets) professional, and at least the international players in major cricketing nations were well-paid.

The first season of the ICL went ahead and was a success in that people watched it. But it was a mess. There was the ICL 20-20 Indian Championship, the ICL 20s Grand Championship, and, perhaps in a tribute to the original World Series, the ICL 20s World Series. A 50-over competition was also in the works but never got off the ground.

By this time the BCCI’s supposed sabotage of the ICL was well underway. They were launching their own franchise league – the IPL – and ensured the walls closed around the ICL. Venues, officials, sponsors were getting harder and harder to find – there were rumours that people were being warned with the prospect of being ignored by the BCCI.

In fact the ‘brain’ behind the IPL, Lalit Modi, would later go on to allege that the BCCI went to the extent of blacklisting service providers like production companies and event managers who worked with the ICL.

Maybe an even bigger blow was landed when the BCCI decided that they would welcome back those who returned from the ICL fold. This meant that those younger domestic players who thought they’d burnt the bridge to an Indian cap, now had a chance to dream of that again.

One guy who came back was Ambati Rayudu. Though his time in the Indian jersey was short-lived, he ended his career as a legend of the IPL, winning five championships for the two most successful franchises in the competition – Mumbai Indians and Chennai Super Kings.

Kapil, whose role in the ICL had cost him his position as the chairman of the National Cricket Academy, did his best to ease tensions between the BCCI and the league. He claimed the ICL would not be a rival or competitor to the board, rather that it would help identify young talent who could go on to play for India – like they were doing the BCCI a favour. Eventually he too was forced to turn his back on the ICL and was formally granted amnesty by the BCCI once he cut all ties with the rebel league.

Even without the BCCI interference, the ICL had issues of its own. The most pressing one was the lack of transparency with finances. Details on contracts and advertising revenue were vague if you could find them at all, and rumours of fixing were rampant. In 2015, former New Zealand batter Lou Vincent admitted that it was in the ICL where he first started fixing matches.

Fixing clearly never went away, but it was louder during the ICL than it had been in a long time. In some matches, it looked like both teams were in on conflicting fixes. A player told me that at one stage Greig came screaming into a changeroom and told one team to stop fixing.

They also kind of abandoned the franchise idea, eventually having games between Pakistan, Bangladesh, India and a World XI. The problem with all this was the quality of the players. Not a single team had a lineup that could compete with their national side. And the World XI was a bunch of players who were stars in the 90s.

After two seasons and four tournaments, unable to sign players and other stakeholders, the ICL eventually ceased to exist. In 2024, it’s easy to forget that it even did. Highlights and scorecards are hard to find, even searching Indian Cricket League on Google will see more results on the IPL than the rebel tournament.

But its impact cannot be denied. It was cricket’s first franchise T20 league, and it gave us silly names and even had the third umpires reviewing each ball. Plus, when the payments were made, the money was really good for domestic cricket, which had never seen riches like that, and it had a knock-on effect on how domestic cricketers were paid.

Over the years, franchise sports in India, not just cricket, have seen a major boom. While the IPL is credited with revolutionising sports broadcasting in the country (franchise leagues for volleyball, football, and even kabaddi now exist), part of that credit should go to the ICL, which, in its own mad, ugly, disorganised, and anarchic way, paved the way for players to be paid more.

But it’s also worth mentioning that while Kerry Packer and Subhash Chandra were fans of cricket, they didn’t do this to pay the players better, but for their own business reasons.

Greig was just a cricketer trying to get paid for his craft and later trying to keep himself employed (even though Packer once said he had a job for life at Channel Nine).

But in many ways, Greig was the Forrest Gump of cricket. Every single big moment over 50 years where our game changed, he was there. When South Africa went away, when ODIs were born, the Packer revolution, and the ICL experiment.

Tony Greig was a fantastically versatile all rounder, and almost maybe the most rebellious. It was perhaps fitting, that he helped kickstart the last major cricket revolution that we’ve seen.